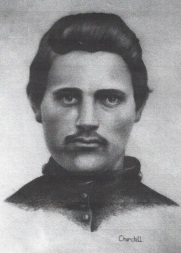

Norvell Francis Churchill – Savior of Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer

- Jim Wade

- December 1, 2017

- 8 Min Read

Norvell Francis Churchill was born June 11, 1840, probably on the family farm which was located near the intersection of Almont and Holmes Roads in Berlin Township, St. Clair County, Michigan. His parents were David Churchill Jr. and Zoa Edgerton Churchill.

Norvell’s fifth-great grandfather, Josiah Churchill, came to America about 1635. He settled in Wethersfield, Connecticut and married Elizabeth Foote in 1638 in Wethersfield.

Norvell’s grandfather, David Churchill Sr. married Seviah or Zereviah Leach on March 6, 1797 in Litchfield, Connecticut. David Sr. moved from Connecticut to Vermont shortly after his marriage. He moved to New York about 1813 and then to Almont in 1836 at the age of 68. David and Seviah had eleven children. When David Sr. moved to Almont several of his adult children also came with him. Their fifth child, Cyrus, was one of the first ministers of the Baptist Church in Almont. David Jr. and Cyrus were living in Ontario, Canada before joining their father in Almont.

David and Zoa would have four children born in Canada: They brought these four children with them from Canada. They would have four more children born in Michigan. Norvell grew up working on the family farm. He probably did not receive much public schooling because the system of schools was not yet established.

On April 15, 1861 President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Norvell enlisted on August 14, 1861 for three years. He was assigned to Company L of the 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment, which was formed by fellow Almonter, Captain Melvin Brewer. At least 43 Almont men enlisted in the 1st Michigan Cavalry. The regiment reached Washington, D. C. on September 29, 1861 and was assigned to the Army of the Potomac.

The first major battle that the 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment was involved in was the Battle of Kernstown on March 23, 1862. Union forces for the first and only time defeated Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson.

After Kernstown, the 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment was assigned to Major General Nathaniel Banks’ command. Norvell was assigned to be one of Banks’ orderlies. The 1st fought in the Battles of First Winchester, Cedar Mountain, and Second Bull Run – all Union losses.

After Second Bull Run, the 1st was transferred to Price’s Independent Cavalry Brigade but Norvell was transferred to be the orderly for Brigadier General Joseph Mansfield, commander of the Twelfth Corp. On September 12th, Norvell had an eye infection and diarrhea. He would eventually lose the eye and have it replaced with a glass eye.

On September 17, 1862 the Battle of Antietam produced the “Bloodiest day in U. S. military history” with nearly 23,000 killed and wounded. One of those casualties was Brigadier General Joseph Mansfield. As Mansfield was leading his men, he was shot in the chest. Private Churchill was at his side and caught the General as he fell from his horse. General Mansfield would die the next day. The Union victory at Antietam gave President Lincoln what he needed to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

After the Battle of Antietam, Norvell was diagnosed with typhoid fever and confined to headquarters for a month. During this time he was orderly to Major General Henry Warner Slocum.

When the Army of the Potomac was being reorganized in June 1863 and the 1st Michigan Cavalry Brigade was being formed, Norvell was assigned as an orderly to their commanding officer. The 1st Michigan Cavalry Brigade consisted of the 1st, 5th, 6th, and 7th Michigan Cavalry Regiments. The Brigade was part of Major General Judson Kilpatrick’s Cavalry Division. On June 29, 1863, a newly promoted Brigadier General was named commander of the 1st Michigan Cavalry Brigade – George Armstrong Custer. General Custer was only six months and six days older than Norvell.

As Custer’s orderly, Norvell would have seen and met the Union officers that interacted with the 1st Michigan Cavalry Brigade. On June 30th, the Brigade saw its first action at the Battle of Hanover.

On July 2nd, Kilpatrick’s Division was searching for a Rebel force located toward the Union right. Custer’s Brigade discovered Wade Hampton’s forces as he was deploying to protect the Rebel left. Custer wanted to draw the Confederates into a trap. To draw the Rebels into the trap, Custer selected Company A of the 6th Michigan. Custer drew his saber and shouted “I’ll lead you this time boys! Come on!” and then spurred his horse down the road. Norvell along with Company A followed.

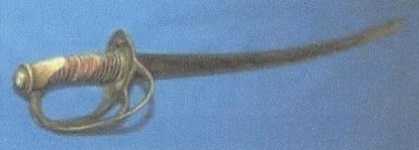

Custer’s his horse was killed and he was pinned under the horse. As Confederate cavalrymen were bearing down on him, Norvell spurred his horse forward. A Rebel came by and swung his saber which Churchill was there to block. The Rebel took another swipe at Custer which Norvell also blocked. Norvell then drew his pistol and shot the Rebel. Norvell then extended a hand to Custer. He pulled Custer up on to the back of his horse and raced back to safety.

In his report on the Michigan Cavalry Brigade at the Battle of Gettysburg, General Custer included a special mention of Norvell. Norvell Churchill’s saber is a prized possession of his descendants. The nicks in the saber from blocking the Rebel’s attempted blows are readily visible.

On July 3rd, Lee’s plan for the day’s battle was for General Pickett to perform a frontal attack on the Union center along Cemetery Ridge while General Stuart’s cavalry attacked from the rear.

General Custer responded to Stuart’s advances by sending a dismounted 5th Michigan forward but they were being overwhelmed. He then ordered a mounted charge by the 7th Michigan, which split the Rebel attack. Stuart responded by bring his entire force forward. Custer, with Norvell at his side, yelled “Come on, you Wolverines” and led the 1st Michigan in a headlong charge into Stuart’s forces. It was reported that the collision was so violent that “horses were turned end over end and crushed riders.” The rest of Custer’s Brigade then attacked Stuart’s flanks. The furious charges by the Michigan Brigade caused Stuart to break off the attack and doomed Pickett’s men to outright slaughter.

On July 2nd, Norvell saved Custer and on July 3rd, the Brigade saved the Union Army. At least three men from Almont died at Gettysburg or in the immediate aftermath. Also, six Almont men were captured at Gettysburg.

Beginning with the Battle of the Wilderness, Norvell was not with the 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment. He was first posted to Grand Rapids where he drilled recruits and later to Jackson, Michigan basically doing recruiting.

After the Civil War, Custer visited Norvell in the late spring of 1874. He traveled by train to Romeo where he was met by Norvell. Custer stayed with Norvell for three days, during which time he tried to persuade his former orderly to re-enlist and join him in the Indian Campaigns. Norvell smartly declined. It is probable that Norvell was courting his future wife, Hannah, at the time of Custer’s visit.

After being discharged, Norvell returned home to the farm. His father had passed away on September 24, 1864. He took over the family farm and helped his brother’s wives with their farms. Peter and Norval split the original 160 acres.

On December 30, 1874, Norvell married Hannah Savage in Romeo, Michigan. Hannah was born near Romeo in Macomb County on October 7, 1851. Norvell and Sarah would have seven children – Elmer, Nellie, Floyd Ray, Maud Estelle, Ina Louise, Harrison David and Hugh Norvil.

Norvell’s mother, Zoa, passed away on September 18, 1877 and was buried next to David in the West Berlin Cemetery. In January 1879, Norvell sold the family homestead and moved his family to Echo Township, Antrim County, Michigan. On his new homestead, Norvell raised cattle and swine. He lumbered off his homestead and eventually planted cash crops.

Once Norvell and Hannah moved to Echo Township, Norvell would ride his horse during parades in Pleasant Valley and nearby villages. He would do tricks: for example, he would drop a handkerchief and then gallop by, lean over, and pick up the handkerchief.

On September 24, 1894, Hannah died while in labor with their eighth child. The child – a little girl – was stillborn. Hannah was buried in the Dunsmore Cemetery in Pleasant Valley. Norvell would live for nearly another twelve years. He died on June 25, 1905 and was laid to rest next to Hannah. It is interesting to note that George Armstrong Custer also died on June 25th but in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Beginning in 2007, an effort began to raise funds to place a commemorative monument for the Battle of Hunterstown. The monument was to honor General Custer and highlight the actions of Norvell in saving his life. On June 2, 2008, 145 years after the battle, the marker was dedicated.